Multimodal Analgesia for Children with Serious Illness: Beyond the "Pharmacology-Only" Approach

By Stefan J. Friedrichsdorf, MD, FAAP*1,2; Eve Golden, MD3

1Department of Pain Medicine, Palliative Care and Integrative Medicine, Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA

2Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA

3Integrated Pediatric Pain and Palliative Care (IP3), UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital, San Francisco, CA, USA

* As of April 1, 2020: Center of Pediatric Pain Medicine, Palliative Care and Integrative Medicine, UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital, Oakland and San Francisco, CA, USA

The three largest groups of children 0-17 years living with and dying from serious illness in North-America are:

- Neonates with prematurity, congenital malformations or chromosomal abnormalities, followed by

- Children with progressive neurodegenerative and chromosomal conditions with central nervous system impairment, followed by

- Children with cancer.

Children enrolled into pediatric palliative care (PPC) programs on average experience nine distressing symptoms, with pain being the most prevalent and most distressing.1-3

The pharmacological approach of using a combination of basic analgesia, opioids and adjuvant analgesia continues to represent the main pillar of state-of-the art pain treatment and its importance cannot be understated. However, it has become clear that for complex pain situations at the end-of-life period “medications only” approaches are often insufficient, and just adjusting the choice, route and dose of analgesics alone is not effective for providing excellent analgesia without over-sedation.

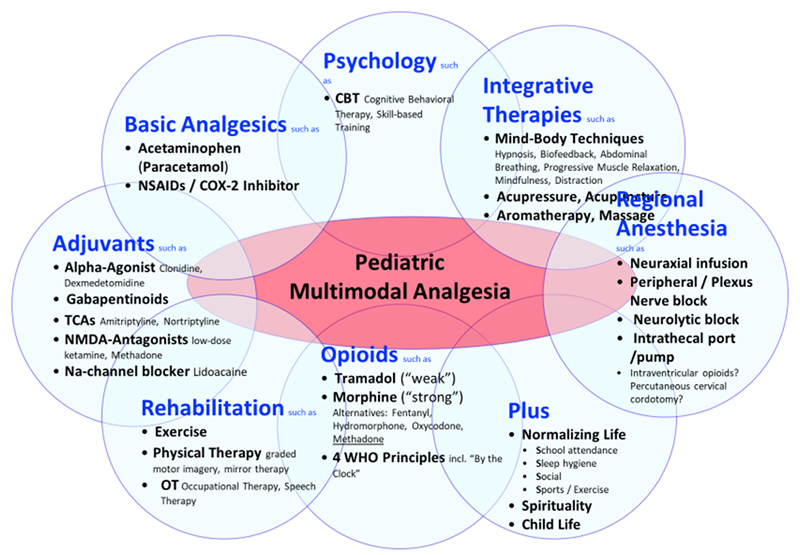

The concept of multi-modal analgesia, initially successfully implemented in the treatment of postoperative acute pain, has now been adapted to pediatric palliative care (see Figure 1), as the “medication only” approach alone is often ineffective and causes a high side effective profile in a significant subset of children with serious illness.

Figure 1: Multimodal Pediatric Analgesia for Children with Serious Illness

Multi-modal analgesia act synergistically for more effective pediatric pain and symptom control with fewer side effects than a single analgesic or modality in children with serious illness and should include, age-appropriately, the following components:

1. Basic Analgesia

Barring contraindications, basic analgesia include acetaminophen and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) or COX-2 inhibitors. Of note, ibuprofen-sodium (available over the counter) requires only half the dose, has analgesic effect within 10 minutes, and its analgesia effect lasts longer.4 Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor might be considered if classic NSAIDs are contraindicated (e.g. owing to bleeding risks, or gastrointestinal side effects).

2. Opioids

Morphine remains the gold standard for medium to severe pain based on tissue injury (or dyspnea). Equally effective alternatives include fentanyl, hydromorphone and oxycodone. A switch from one opioid to another is often accompanied by a change in the balance between analgesia and side effects.5 Opioid-associated side effects (e.g. constipation, pruritus, and nausea) should be anticipated and treated accordingly.

Two potentially particularly effective multi-mechanistic opioids include the “weak” tramadol (for mild to medium pain) and “strong” methadone.6 Tramadol appears to play a key role not only in outpatient surgery (due to its relative respiratory safety, more than 6,000 pediatric tramadol scripts were filled at Children’s Minnesota in 2018) but especially in treating episodes of inconsolability in children with progressive neurologic, metabolic or chromosomally-based conditions with impairment of the central nervous system.6 However, the recent 2017 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning against pediatric use of tramadol does not seem to be based on clinical evidence (three children died worldwide in 49 years and therefore it appears far safer than any other opioid). Unfortunately, this warning may place children at greater risk for unrelieved pain and other distressing symptoms.7

Methadone, due to its multi-mechanistic action profile, is possibly among the most effective and most underutilized opioid analgesics in children with severe unrelieved pain, especially in patients receiving palliative care. However, methadone should not be prescribed by those unfamiliar with its use: Its effects should be closely monitored for several days, particularly when it is first started and after any dose changes.6,8-10

3. Adjuvant Analgesia

Effective adjuvant analgesia include alpha-2-adrenergic agonists (e.g. clonidine or dexmedetomidine), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) channel blocker (e.g. low-dose ketamine), gabapentinoids (gabapentin or pregabalin), low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline or nortriptyline), and/or sodium-channel blocker (e.g. lidocaine).

Cannabinoids, including cannabidiol [CBD] and tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] lack sufficient evidence to support its use for acute, neuropathic or chronic pain.11,12 The updated American Academy of Pediatrics policy opposes marijuana use,13 citing lack of research and potential harms including correlation with mental illness, testicular cancer, decline in IQ, and increased risk of addiction. In our clinical practice, we do not support the use of marijuana (or medical cannabis) for a child with a primary pain disorder and a normal life expectancy. However, in children with life-limiting conditions, the administration of medical cannabis is often requested by patients and their parents, and certainly may be considered on a case-by-case basis. It is important to watch carefully for side effects (including pancreatitis, psychosis etc.).

4. Integrative (“non-pharmacological”) Treatment Modalities

Integrative (sometimes called “complementary” or “alternative”) medicine modalities need to be appropriate to the age and the child’s cognitive development. Skin-to-skin contact and non-nutritive (sucrose) sucking are highly effective for infants.14 Modalities for toddlers, school children and young adults that have shown to be effective in treating and preventing pediatric pain include deep breathing, biofeedback, self-hypnosis, yoga, acupuncture, and massage.15-25 These active mind-body techniques, such as guided imagery, hypnosis, biofeedback, yoga, and distraction may result in pain reduction through involvement of several mechanisms simultaneously within the analgesic neuraxis. Additionally, healing approaches to working with pain and symptom distress such as music therapy, art therapy and animal-assisted therapy have been studied to some extent in children with complex chronic disease and have been shown to help with pain, anxiety and coping.26-31

5. Exercise, Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation

Physical therapy and exercise are key modalities in the treatment of patients with pediatric palliative care. Graded Motor Imagery, including mirror therapy, is the process of thinking about moving without actually moving, and has been shown especially effective in children with serious illness.32

6. Psychological Interventions

Anxiety, depression, catastrophizing and behavioral disorders represent risk factors for pain development in children and adolescents with serious illness. For children who have the expressive and receptive language capabilities necessary to engage in these interventions, the importance of psychological services can hardly be understated. Either way, psychological service to healthy siblings and parents/caregivers should be offered.

7. Spirituality

Parents of children receiving palliative care described religion, spirituality and/or life philosophy playing an important role in their life and that of the affected child32. A correlation between spiritual coping and the quality of life in pediatric patients with chronic serious illness has been described.33,34 Most children’s hospitals encourage the inclusion of spiritual aspects of life into healthcare, including making hospital chaplains available.

8. Regional Anesthesia

One of the most effective analgesic modalities in children with tissue injury represents regional or neuroaxial anesthesia. Nociceptive pathways may be blocked utilizing central neuraxial infusions, peripheral nerve and plexus blocks or infusions, or neurolytic blocks.35 There are relatively few studies in pediatric populations regarding the use of interventional techniques for pain management. However, many studies of adult patients have taken place which have documented improvement in pain management. Adult studies have looked at many interventional approaches to pain control including neuroaxial analgesia, minimally invasive procedures for vertebral pain (vertebroplasty, kyphoplasty, cryoablation), sympathetic blocks (celiac plexus and hypogastric nerve blocks for abdominal pain), paravertebral blocks, blocks in the head region, plexus blocks, and intercostal blocks as well as cordotomy. These procedures not infrequently may have contraindications and complications thus their use in pediatric populations remains limited and less well studied.

Conclusion

Advanced pain treatment and prevention for children in pediatric palliative care in the 21st century must go beyond the “medications only” approach. Effective multimodal analgesia for persistent pain in children with medical illnesses act synergistically for more effective pediatric pain control with fewer side effects than single analgesic or modality and includes pharmacology (e.g. basic analgesia, opioids, adjuvant analgesia), regional anesthesia, rehabilitation, psychology, spirituality, as well as integrative (“non-pharmacological”) modalities.

REFERENCES

- Wolfe J, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Symptoms and Distress in Children With Advanced Cancer: Prospective Patient-Reported Outcomes From the PediQUEST Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1928-1935.

- Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier AC, Andrews GS, Hamre KE, Steele R, Siden H. Pain reporting and analgesia management in 270 children with a progressive neurologic, metabolic or chromosomally based condition with impairment of the central nervous system: cross-sectional, baseline results from an observational, longitudinal study. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1841-1852.

- Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, et al. Pediatric palliative care patients: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 2011;127(6):1094-1101.

- Moore RA, Derry S, Straube S, Ireson-Paine J, Wiffen PJ. Faster, higher, stronger? Evidence for formulation and efficacy for ibuprofen in acute pain. Pain. 2014;155(1):14-21.

- Drake R, Longworth J, Collins JJ. Opioid rotation in children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(3):419-422.

- Friedrichsdorf SJ. From Tramadol to Methadone: Opioids in the Treatment of Pain and Dyspnea in Pediatric Palliative Care. Clin J Pain. 2019.

- Friedrichsdorf SJ. From Tramadol to Methadone: Opioids in the Treatment of Pain and Dyspnea in Pediatric Palliative Care. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(6):501-508.

- Fife A, Postier A, Flood A, Friedrichsdorf SJ. Methadone conversion in infants and children: Retrospective cohort study of 199 pediatric inpatients. J Opioid Manag. 2016;12(2):123-130.

- Madden K, Bruera E. Very-Low-Dose Methadone To Treat Refractory Neuropathic Pain in Children with Cancer. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(11):1280-1283.

- Mercadante S, Bruera E. Methadone as a First-Line Opioid in Cancer Pain Management: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(3):998-1003.

- Hill KP. Medical Marijuana for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Other Medical and Psychiatric Problems: A Clinical Review. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2474-2483.

- Deshpande A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Zoheiry N, Lakha SF. Efficacy and adverse effects of medical marijuana for chronic noncancer pain: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(8):e372-381.

- Pediatrics AAo. Updated AAP policy opposes marijuana use, citing potential harms, lack of research. 2015; http://aapnews.aappublications.org/content/early/2015/01/26/aapnews.20150126-1.

- Campbell-Yeo M, Johnston CC, Benoit B, et al. Sustained efficacy of kangaroo care for repeated painful procedures over neonatal intensive care unit hospitalization: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2019.

- Bussing A, Ostermann T, Ludtke R, Michalsen A. Effects of yoga interventions on pain and pain-associated disability: a meta-analysis. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2012;13(1):1-9.

- Evans S, Moieni M, Taub R, et al. Iyengar yoga for young adults with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a mixed-methods pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(5):904-913.

- Vas J, Santos-Rey K, Navarro-Pablo R, et al. Acupuncture for fibromyalgia in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2016.

- Verkamp EK, Flowers SR, Lynch-Jordan AM, Taylor J, Ting TV, Kashikar-Zuck S. A survey of conventional and complementary therapies used by youth with juvenile-onset fibromyalgia. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14(4):e244-250.

- Friedrichsdorf S, Kuttner L, Westendorp K, McCarty R. Integrative Pediatric Palliative Care. Oxford University Press; 2010.

- Kuttner L, Friedrichsdorf SJ. Hypnosis and Palliative Care. In: Therapeutic Hypnosis with Children and Adolescents. 2nd ed. Bethel: Crown House Publishing Limited; 2013:491-509.

- Hunt K, Ernst E. The evidence-base for complementary medicine in children: a critical overview of systematic reviews. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(8):769-776.

- Evans S, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. Complementary and alternative medicine for acute procedural pain in children. Altern Ther Health Med. 2008;14(5):52-56.

- Richardson J, Smith JE, McCall G, Pilkington K. Hypnosis for procedure-related pain and distress in pediatric cancer patients: a systematic review of effectiveness and methodology related to hypnosis interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(1):70-84.

- Friedrichsdorf SJ, Kohen DP. Integration of hypnosis into pediatric palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7(1):136-150.

- Evans S, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. Paediatric Pain Management: Using Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Rev Pain. 2008;2(1):14-20.

- Whitehead-Pleaux AM, Zebrowski N, Baryza MJ, Sheridan RL. Exploring the effects of music therapy on pediatric pain: phase 1. Journal of music therapy. 2007;44(3):217-241.

- Madden JR, Mowry P, Gao D, Cullen PM, Foreman NK. Creative arts therapy improves quality of life for pediatric brain tumor patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2010;27(3):133-145.

- Derman YE, Deatrick JA. Promotion of Well-being During Treatment for Childhood Cancer: A Literature Review of Art Interventions as a Coping Strategy. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(6):E1-E16.

- Silva NB, Osorio FL. Impact of an animal-assisted therapy programme on physiological and psychosocial variables of paediatric oncology patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194731.

- Gilmer MJ, Baudino MN, Tielsch Goddard A, Vickers DC, Akard TF. Animal-Assisted Therapy in Pediatric Palliative Care. Nurs Clin North Am. 2016;51(3):381-395.

- Kurita GP, Sjogren P, Klepstad P, Mercadante S. Interventional Techniques to Management of Cancer-Related Pain: Clinical and Critical Aspects. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(4).

- Ramsey LH, Karlson CW, Collier AB. Mirror Therapy for Phantom Limb Pain in a 7-Year-Old Male with Osteosarcoma. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(6):e5-e7.

- Grossoehme DH, Szczesniak R, McPhail GL, Seid M. Is adolescents' religious coping with cystic fibrosis associated with the rate of decline in pulmonary function?-A preliminary study. J Health Care Chaplain. 2013;19(1):33-42.

- Reynolds N, Mrug S, Guion K. Spiritual coping and psychosocial adjustment of adolescents with chronic illness: the role of cognitive attributions, age, and disease group. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):559-565.

- Rork JF, Berde CB, Goldstein RD. Regional anesthesia approaches to pain management in pediatric palliative care: a review of current knowledge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(6):859-873.