COVID-19

Providing Needleless Acupuncture Telemedicine During COVID-19

By Yuan-Chi Lin, MD, MPH and Cynthia Tung, MD, MPH

Medical Acupuncture Service

Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine

Boston Children’s Hospital

Department of Anaesathesia

Harvard Medical School

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first case was reported in China on December 8, 2019. The Chinese government verified that doctors in Wuhan, China were treating dozens of patients by the end of December 2019. Within days, the new virus of the family Coronaviridae possessing a single-strand, positive-sense RNA genome was identified. At that time, the World Health Organization stated that “there was no evidence that the new virus was readily spread by humans, which would make it particularly dangerous, and it has not been tied to any deaths.” Little did we know, the global public health emergency caused by the coronavirus would unfold rapidly and dramatically.

In early March, the Governor of Massachusetts issued a State of Emergency order. Public as well private schools were closed. All non-essential worker citizens were asked to stay at home and practice social distancing. The hospital instructed physicians to minimize elective visits, admissions, and procedures. We had a clear obligation to help keep families whose needs were not urgent at home, and to do our part to slow the spread of COVID-19 throughout the communities we served. As part of that responsibility, we continued to provide care for those in need, while protecting our clinic staff, and transformed our Medical Acupuncture Service at Boston Children’s Hospital into a telehealth, virtual clinic.

Acupuncture originated from China and is a part of traditional Chinese medicine. Acupuncture is commonly used in China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. In many developed countries, it is also available as one of the complementary medical therapies, and integrated into routine medical care. Recognizing our contemporary knowledge of neuromuscular anatomy and pain physiology, we incorporate the classical Chinese perception of a subtle qi circulation network into modern medicine.1

The basic concept is qi, which is usually, though incompletely,interpreted as “energy”. It is believed that the qi is inherited at birth and preserved during life by intake of food and air. It circulates throughout the body and nourishes as well as defends body parts. Acupuncture is to unblock the blockage of qi, facilitate the qi flow and balance the body's yin and yang. Diseases are associated with disharmony and disturbance of Yin and Yang. The NIH Consensus Conference in acupuncture concluded that there is efficacy in using acupuncture in pain control.2

The following describes our experience at Boston Children’s Hospital in creating and using a telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic for new and existing acupuncture patients.

Telemedicine Preparation

The preparation for a telemedicine consultation should be similar to what we commonly would plan for a patient’s in-person clinic visit. We reviewed the patient’s medical records, patient pre-registration materials, and any available imaging studies to understand his or her disease processes and the reasons for referral.

Clinicians can sit at home or in the office, and the patient and patient’s family can complete their visit from their own home. We made sure the environment was not too bright by adjusting our own ambient light source, and by silencing other sources of sound. Boston Children’s Hospital provided a hotline number for providers and patients for urgent computer-related problems. For times when we had trainees participating in telehealth visits, we set up proper three-way internet linking systems.

Telehealth Visit

The history obtained for the telehealth visit was similar to the in-person clinic meeting. We inquired about the chief complaint, reviewed the past medical history, current medications, allergies, past surgical history, family history, and social history.

The physical examination is limited; however, we could ask them to obtain their own weight with a home scale or take their own blood pressure with a home device, if deemed necessary.

We assessed the patient’s general appearance, which also gives us information of their interaction with their home environment. For example, if we would see a patient with chronic pain lying in bed during every telehealth visit, we could give suggestions about making inactivity and lifestyle adjustments, as well as behavioral modifications.

With many pediatric patients on our service with chief complaints of headaches, the neurologic examination can also be completed through telehealth.

We can assess patient’s mental status, which includes alertness, appropriateness with examiner, and following commands. The cranial nerve examination can be evaluated, by looking at the pupils, inspecting eye movements including evidence of nystagmus, and looking for ptosis. The patient or parent can assist in assessing light touch to facial regions. We observe and verify the facial movements, and symmetric activation with smile. We can confirm gross hearing is normal. The patient can open the mouth to the camera for examination of palate and tongue. We can also ensure dysarthria is absent. We can evaluate extremity movements in all directions. We can look for tremors. We can also check finger-to-nose test, heel movement knee to shin, rapid alternating movement, Romberg test, gait, tandem walking and balancing on heels and toes.

Pain Management Plans and Needleless Acupressure Treatment

After the history and virtual physical examination, we summarized the disease processes, explained to the patient and family the normal physiology of pain, and educated them on the mechanisms of developing abnormal pain responses. If necessary, we ordered additional consults or imaging studies. We then created the pain management strategies, including available conventional medical therapies, behavioral medical therapy, physical therapy, lifestyle adjustment, meditation methods, relaxation strategies, and acupuncture/acupressure treatment.

In the Medical Acupuncture Service, we formulated the telemedicine needleless acupuncture, acupressure, treatment plan, then taught one, but no more than two, major acupressure points at each virtual visit. We identified the acupuncture points and demonstrated the acupressure techniques. Acupressure is pressing and rubbing on the acupuncture point to produce adequate pressure but not to elicit pain sensation. Frequently, we prepared diagrams of each acupuncture point and presented it to the patient and family. If appropriate, we asked patients to do acupressure by themselves or would teach a parent how to provide acupressure. We asked patients to provide acupressure for three minutes, three times a day; for example, after breakfast, after lunch and before going to sleep. While school is in session, we recommend doing acupressure on the way to school and on the way back from school. The goal of acupressure is to prevent or reduce/stop the pain, and patients may perform additional acupressure for episodic discomforts.

We asked patients to keep a pain diary, and scheduled follow-up visits once a week or once every other week to ensure patients are providing proper acupressure.

For those patients being admitted in the hospital, we provided in-patient virtual services during our COVID-19 State of Emergency. We set up a virtual zoom connection with the in-patient primary care team. We reviewed the medical record and contacted the primary care nurse for an update of medical condition. We communicated virtually with the patient and/or family to obtain additional history as well as verbal consent. We then discussed some major acupuncture points with the primary nurse, such that the nurse would provide acupressure for the patient.

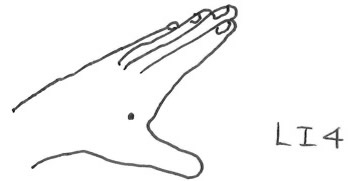

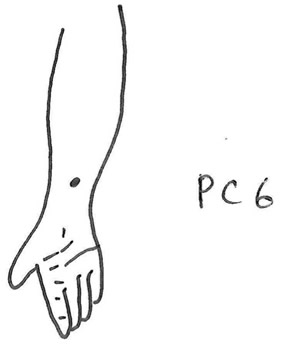

The following are two examples of the acupuncture points commonly utilized for acupressure.

The illustrations show important acupuncture points that are used when applying acupressure.

Simple hand finger pressure is applied and there are no devices, pins/needles or creams/lotions/rubbing alcohol required.

PC 6 (nei guan; “major gateway of internal organ”) is located 2 to 3 tsun above the transverse crease of the wrist, a deep depression between the tendons of the long palmar muscle and the radial flexor muscle of the wrist.

Results

Over the three-month period during the peak of COVID-19 in the state of Massachusetts, our Medical Acupuncture Service provided telehealth visits or consultations to 26 patients, aged 8 to 28. The male-to-female ratio was 1:4. Seventy percent of the patients had a history of headache, with the majority diagnosed with tension headaches. More than half of our patients had anxiety disorders.

Providing telemedicine virtual care is an enormous commitment. Throughout the thirty-minute visit, we were very engaged with the patient and his/her family. We wanted every moment to be useful and high-yield for the patients. Pediatric patients with pain-related illnesses require family support and encouragement, so parental involvement is also important. We received many comments about how parent and child can spend quality time together by doing acupressure, especially during this COVID-19 era. With many patients, we were able to communicate with their primary care services to taper their pain medications. As a result of creating this telehealth program, we were able to continue to provide our patients with decreased discomfort, increased activity level, and a better quality of life during this uncertain time.

Discussion

Acupressure, a.k.a. Zhe Ya or Tuei-Nai, is part of traditional Chinese medicine. This is based on acupuncture, Zan Fu, and meridian theory, using hand pressure to normalize physiological functions, improve pathological conditions, and produce therapeutic effects. Acupressure is applying finger pressure over the acupuncture points. There is no need to use any additional equipment. It heavily relies on parents when applying acupressure to nonverbal or younger pediatric patients.

Acupuncture and acupressure can be utilized for prevention and treatment for nausea/vomiting, perioperative care, as well as headache management. For patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures, acupressure reduced the incidence of nausea or vomiting from 42% to 19% .3 Rusy et al. studied postoperative nausea in 120 pediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy. This study indicated that electro-acupuncture reduced the incidence of nausea with a treatment effect as powerful as that of pharmacologic therapies.4

Perioperative usage of acupuncture can also be applied in the pediatric population.5 A prospective randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of acupuncture to control pain and agitation after initial bilateral myringotomy tube placement in 60 non-premedicated children showed acupuncture provided significant benefit in pain and agitation reduction.6 Lao et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial in evaluating the efficacy of acupuncture in treating postoperative oral surgery pain.7 A systematic review of fifteen randomized controlled trials comparing acupuncture and related techniques for postoperative pain indicated that postoperative pain intensity was significantly decreased in the acupuncture group as compared with the control group.8

Acupuncture therapy for migraine headaches has been reported to be effective in several adult studies. In a randomized controlled trial of 160 women with migraines, acupuncture was proven to be adequate for migraine prophylaxis. Relative to flunarizine, acupuncture treatment exhibited greater efficacy in the first months of therapy and better patient tolerance.9 A systematic review of 22 trials including a total of 1,042 patients suggests that acupuncture has a role in the treatment of recurrent headaches.10 In a randomized controlled trial of 401 patients with chronic migraine headaches, it was also shown that through 12 months of follow-up that acupuncture was relatively cost-effective.11 Cochrane database of systematic review of 11 trials with 2,317 patients with episodic or chronic tension-type headache revealed that acupuncture could be a valuable non-pharmacologic tool in patients with frequent episodic or chronic tension-type headaches.12 In regard to acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis, meta-analysis of 22 trials with 4,419 participants showed acupuncture to be at least as effective and possibly more effective than prophylactic drug treatment with fewer adverse effects. Acupuncture should be considered an option for patients willing to undergo this treatment.13

Telemedicine is defined as using the tele-communications technologies to provide medical information and services. It has been under development for over sixty years.14 A randomized controlled trial indicates that telemedicine consultation for non-acute headache is as efficient and safe as traditional consultation.15 A prospective pediatric telemedicine study indicates that telemedicine is a convenient, cost-effective, and patient-centered. It results in high patient and family satisfaction.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has driven rapid changes in many areas of healthcare. Due to the risks of spreading SARS-CoV-2 virus, patients are losing access to some healthcare and services due to the inability to present to clinics in-person. Adequate pain control through acupuncture is one such service with a well-established need by our current patients, as well as a service with increasing demand in our patient population. Needleless acupuncture, acupressure, can be successfully applied by parents to their children with excellent responses, especially when given with loving kindness.17 Telemedicine and remote monitoring advances will persist after the COVID-19 pandemic.18 We believe that telemedicine can be effectively utilized in delivering acupressure care for pediatric patients.

References

- Helms JM. An overview of medical acupuncture. Altern Ther Health Med 1998;4:35-45.

- NIH Consensus Conference. Acupuncture. JAMA 1998;280:1518-24.

- Harmon D, Gardiner J, Harrison R, Kelly A. Acupressure and the prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopy. Br J Anaesth 1999;82:387-90.

- Rusy LM, Hoffman GM, Weisman SJ. Electroacupuncture prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting following pediatric tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy. Anesthesiology 2002;96:300-5.

- Lin YC. Perioperative usage of acupuncture. Paediatr Anaesth 2006;16:231-5.

- Lin YC, Tassone RF, Jahng S, et al. Acupuncture management of pain and emergence agitation in children after bilateral myringotomy and tympanostomy tube insertion. Paediatr Anaesth 2009;19:1096-101.

- Lao L, Bergman S, Hamilton GR, Langenberg P, Berman B. Evaluation of acupuncture for pain control after oral surgery: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:567-72.

- Sun Y, Gan TJ, Dubose JW, Habib AS. Acupuncture and related techniques for postoperative pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:151-60.

- Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico PE, et al. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache 2002;42:855-61.

- Melchart D, Linde K, Fischer P, et al. Acupuncture for recurrent headaches: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cephalalgia 1999;19:779-86; discussion 65.

- Vickers AJ, Rees RW, Zollman CE, et al. Acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care: large, pragmatic, randomised trial. BMJ 2004;328:744.

- Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of tension-type headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD007587.

- Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016:CD001218.

- Perednia DA, Allen A. Telemedicine technology and clinical applications. JAMA 1995;273:483-8.

- Muller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. A randomized trial of telemedicine efficacy and safety for nonacute headaches. Neurology 2017;89:153-62.

- Qubty W, Patniyot I, Gelfand A. Telemedicine in a pediatric headache clinic: A prospective survey. Neurology 2018;90:e1702-e5.

- Aung SKH. Pediatric Acupuncture: A Spiritual Perspective. Med Acupunct 2019;31:334-8.

- Bloem BR, Dorsey ER, Okun MS. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Crisis as Catalyst for Telemedicine for Chronic Neurological Disorders. JAMA Neurol 2020.